This year, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been struggling for re-authorization because Republicans have been blocking sections that create policy specific to supporting Native, immigrant, and LGBT survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Specifically, these sections help make non-Native men who assault Native women on tribal lands subject to prosecution by tribal courts; provide undocumented survivors who cooperate with prosecuting their abusers with U-visas; and support access to legal and victim services to LGBT survivors, including training police and other law enforcement personnel.

I have no doubt that these Senators are blocking these provisions ultimately because of their contempt for these populations. Importantly, their contempt is institutionally sanctioned by colonial, genocidal, xenophobic, and homo/transphobic projects that have helped license who can and can’t be considered legitimate victims of violence.

That said, I’m frustrated by uncritical pro-VAWA advocacy by progressive and feminist voices. The argument is that all survivors deserve “equal access” to the “protection” that VAWA offers. The anti-racist position seems to begin and end with the idea that we should urge Senators to pass the “good” version of VAWA that includes these provisions. However, this argument fails to ask if state-based “protection” is helpful for those people who cannot access racist notions of legitimate survivorhood. This “good” VAWA vs racist/homophobic VAWA framing obscures the fact that VAWA itself is tied to devastating legacies of racial violence.

VAWA directs federal funding to investigate, arrest, and prosecute those deemed guilty of domestic violence and sexual assault, as well as provides federal funds to services. It was initiated in 1994 as part of the behemoth Crime Bill Act which, as Angela Davis put it, facilitated the incarceration of more women. This was especially true for black and Latina women, who, by 2005, were 200% and 69% (respectively) more likely than white women to be incarcerated. In short, the ‘94 Crime Bill and anti-violence feminists’ advocacy for criminalization-based strategies in general, was a catastrophe for many survivors of color. This has been discussed at length here, here, here, and here, as a few examples.

Black feminist anti-violence veteran and scholar Beth Richie also discusses this legacy in her recent book, Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and America’s Prison Nation. She writes:

Paradoxically, the social commitment to incapacitation, surveillance, and criminal justice sanctions, which were not originally key elements of the anti-violence movements’ radical agenda, were accepted as necessary strategies in order to benefit some women at the expense of others who are less advantaged. Once divestment has begun and movements are being co-opted, isolation and criminalization constitute the final and most significant aspect of the buildup of a prison nation and its impact on Black women who experience male violence.

…instead of benefiting from advances in state protection when they are in danger, Black women from low-income communities become isolated from mainstream services, blamed for the abuse they experience, and then sanctioned by state agencies for the harm they endured. (pp 111-112)

State-driven, pro-criminalization strategies to address domestic and sexual violence doesn’t just limit black women’s “access” to anti-violence services or justice, it reinforces and legitimizes state violence against black survivors. In an earlier book, Compelled to Crime: The Gender Entrapment of Battered Black Women, Richie outlines how the survival tactics of black women domestic violence survivors are systematically criminalized, ultimately landing them in prison. As I’ve argued elsewhere, when black women are victims of violence, they are constantly dis-positioned as the perpetrator of the crime of violence. Ask Marissa Alexander, who is serving 20 years for shooting at a wall as a self-defense warning to her abusive husband. Or CeCe McDonald who is in jail for defending herself from racist and transphobic white people who slashed her in the face. Or the New Jersey 7, black lesbians who were prosecuted and convicted for defending themselves from a street attack. Or Janice Wells who, after being profiled as a domestic violence victim by police, was pepper-sprayed and tasered by those officers.

So I ask those who are advocating for VAWA in order for survivors to gain “equal access”: equal to whom and access to what?

Further, Richie’s assertion that anti-violence feminist activists pursued criminalization at the expense of those survivors who are routinely targeted for police/prison violence highlights a racial politics of survivor currency. Namely, if the state is fundamentally organized around anti-black racism and settler colonialism which systematicallybrutalizessomesurvivors in order to secure the provisional “safety” for others, what kind of trade agreement are anti-violence advocates co-signing and helping to authorize?

Instead of uncritical support of law-and-order legislation like VAWA, I wish that feminist advocates would promote a politics grounded in racial justice that address the profound structural conditions that help drive domestic and sexual violence for so many of us. A politics that says yes to making sure that non-Native men cannot abuse Native women and others with impunity through the restoration of sovereignty that ultimately creates space to develop community-based responses to violence and doesn’t further empower the colonial state (as advocated by Andrea Smith and Sarah Deer). And yes to amnesty for undocumented immigrants who are survivors of violence (among others), but not dependent on their coerced participation with police and prosecutors, as would be required from the “good” version of VAWA. And yes to the public recognition of the existence of queer relationships and access to services for queer survivors of domestic and sexual violence, but why hinge that recognition to a state that regularly and intentionally wields violence against queer people of color who are poor, incarcerated, immigrants, indigenous, disabled, and/or black? (More on that visionary politics here.) And critically, yes to pushing back against the state’s invitation to be complicit in “crime control” policies that we know — and have known — terrorize black survivors and others whose bodies are routinely targeted by the state.

It would be powerful if anti-violence feminists would develop a politics that seamlessly integrated our work into social movements that support Native sovereignty, (im)migrant justice, and queer liberation. It would also be transformative (not to mention a great spiritual relief to me personally) if anti-violence feminists would concurrently nurture a deep and genuine commitment to black freedom. While this (still) requires fundamental shifts in the politics and praxis of much of the network of anti-violence programs, I think practical strategies are available to policy advocates who are serious about working towards these goals. For example, what would happen if advocates demand that federal funding for services come with no strings attached to state-based crime control policies? Receiving funding from the state has its own serious problems, so this move should be considered an intermediate step towards a more liberatory and liberated anti-violence social movement that isn’t beholden to the state at all. But a partial divestment designed to intentionally reject what Richie calls the “prison nation” might create a strategic fissure between anti-violence efforts and a state apparatus that is unbearably hostile towards so many survivors of domestic/sexual violence.

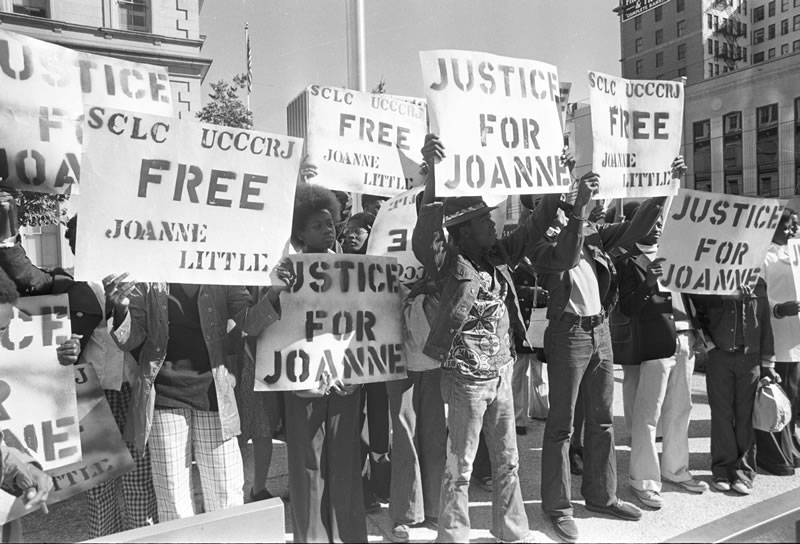

Finally, I feel like I should note that the concerns that I’m raising here are not new and reflect decades of critiques offered by black feminists, indigenous feminists, other radical feminists of color, and many other critical voices. And yet, here’s everyone demanding that we all get our VAWA on. That these critiques continue to go unheeded or are tacitly dismissed leads me to believe that black women are near-incapable of being seen and valued by the broader community of people working to address domestic and sexual violence. Not only have the consequences of criminalization and other collaborations with the state remained largely unaddressed, they are barely recognized at all these twenty years post-VAWA, and all these books, studies, conferences, forums, media, and organizing labor later. I mean, for the love of Joan Little, people. What exactly does it take for us to get there?

↧

vawa - a black feminist dissent

↧